This book is a detailed account of the life-long experience in aquatic

ecosystem rehabilitation of the Swedish limnologist Sven Björk, who is

also the principal author. The narrative of the book is centered

around some major examples, of which two are lakes in southern Sweden

and six others are lakes and wetlands in different parts of the world,

that is Brazil, China, Tibet, Jamaica, Tunisia, and Iran. Because of

the long time-span covered by his active career, Björk’s stories read

more like a history of the growth of limnological insights and their

applications to solve major environmental problems during the period

1955–2012. Most attention is paid to the two lakes closest to the

author’s home, that is Lake Trummen near Växjö and Lake Hornborga in

Västergötland. These lakes are each an example of a major

environmental deterioration of lake systems in this part of the world

in the 1950s–1960s; Lake Trummen was heavily eutrophicated because of

increasing inflows of domestic wastewater, whereas Lake Hornborga

suffered from seriously lowered water levels to reclaim agricultural

land in the surrounding peaty catchment. For both lakes, there is an

impressive account of the problematic initial situation, the careful

application of knowledge and research for designing rehabilitation

plans, the implementation of these plans in often innovative

technological and ecological measures, and the monitoring of the lake

condition towards a sustainable, healthy status. For the Hornborga

Lake, this involved attempts to stop and reverse the massive

colonization of the shallower lake by aquatic plants and reeds. These

courses of events spanned more than 50 years and were all meticulously

recorded and described, with attention for the changes in ecological

functioning, plant and animal diversity, for the communication with

stakeholders and society at large, and for the successes and failures

in working together with engineers and politicians.

The sections about the various projects of much shorter duration in

widely different parts of the world give an overview of the contacts

of Björk and his group with the outside world, as they developed

during his lifetime. Often the group was called in for help to solve

major problems by fellow limnologists who had obviously been impressed

by the major accomplishments in the Swedish lakes and wetlands. Björk

and his team worked on a rehabilitation plan for the heavily polluted

Lake Tunis (1970s) and were invited by the Iranian government to

develop plans for the rehabilitation of wetlands and lakes threatened

by droughts and pollution in Pahlavi/Mordab Lagoon near the Caspian

Sea (1970s). In both of these projects, studies were made and ideas

for whole suites of large-scale measures were proposed, but these did

not materialize because of political issues and (in the case of Iran)

regime change. There are nice descriptions (by Wilhelm Granéli) of

restoration projects in several degraded lakes in Brazil

(1980s/1990s), while two projects stand out because they deal with

several large peatlands in different parts of the world undergoing

nonsustainable exploitation. The Swedish team was asked to develop a

more holistic scheme for making use of the natural resources of the

peatlands without the major deterioration of the areas. The projects

in the mountains of Tibet and in Jamaica (1980s/1990s) had to deal

with the practice of peat excavations to use it for fuel and for

horticultural purposes. It is striking that the rehabilitation plan

here called for a better distinction of the peat types in the area

suitable for the horticultural use or for burning, not for minimizing

all uses of peat. It should be noted here that the importance of

peatlands to store carbon and to regulate regional climate is now

widely accepted, and drainage and use of peat are inherently

nonsustainable because the resource is depleted (and converted to CO2)

immensely faster than it is replenished by peat growth. It is

striking that the Swedish team obviously had different standards for

sustainable use for lakes and for peatlands here.

The book is closed off with a chapter on “issues aggravating

anthropocenic nature,” which is a compilation of often harsh

statements and opinions by the author, probably borne partly from

large challenges and even frustrations during his long journey aiming

at improving the balance between human activities and nature’s

integrity. This account of battles fought mostly in the Swedish arena

mentions, for instance “lack of competence within the environmental

judicial system,” “the government’s consideration of

‘permissibility,’” the need to consider problems in a holistic,

landscape/catchment-wide way, and a detailed report of the battle

against the plan for a highway through a wetland.

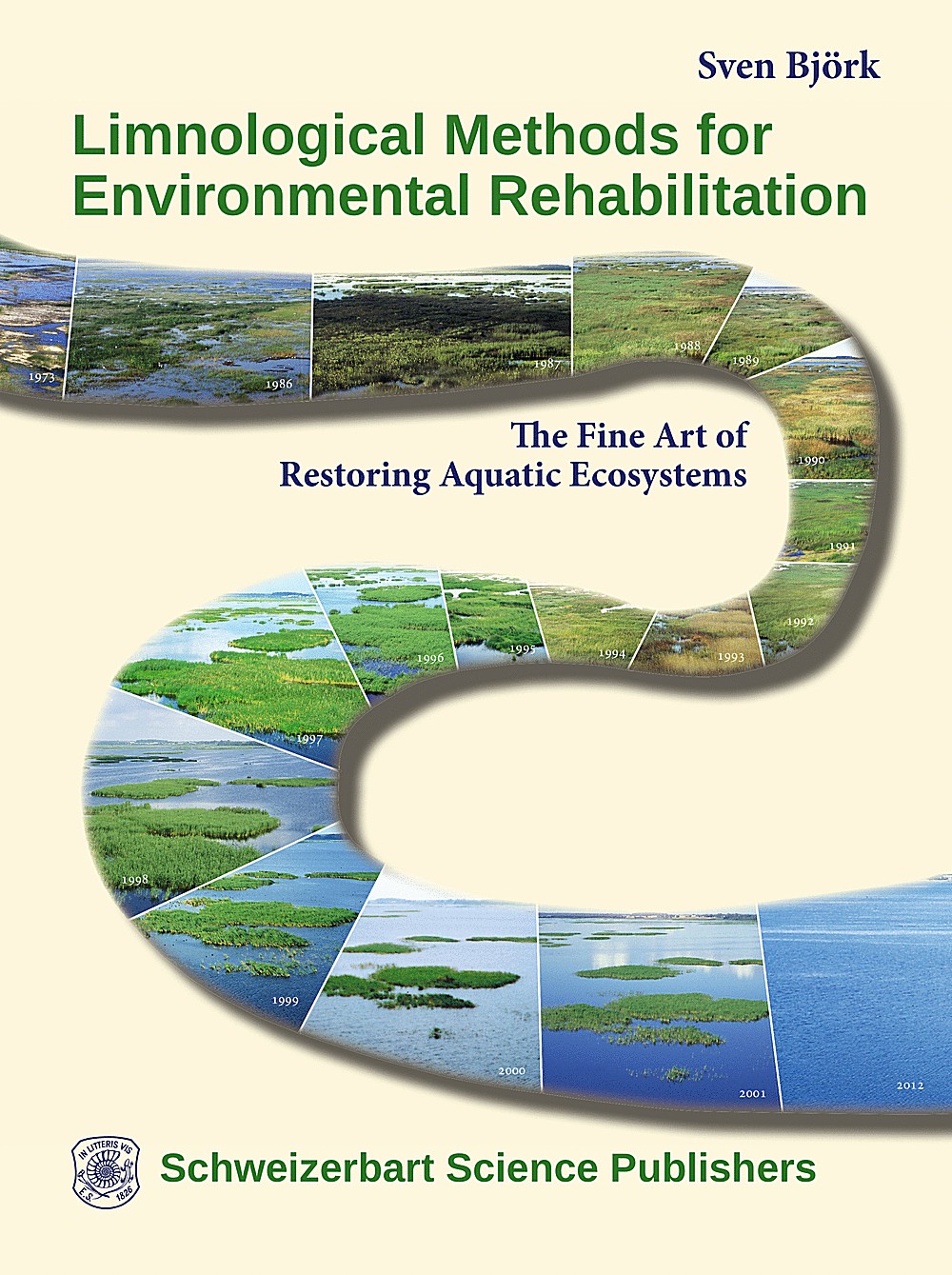

As will be clear from the above, the book is very much dominated by

the spirit and passion of Sven Björk. It has an impressive number of

detailed stories on ways to repair a devastated landscape with lakes

and wetlands. It is very well illustrated with many good pictures and

graphs. In particular, the series of pictures taken at the same spot

over a very large number of years clearly show how drastic changes

over time can be. They are really unique. A downside of the book is

that the many examples and case studies are often described in great

detail and do not follow a common approach. Some case studies are

quite accessible with a clear introduction, presentation of objectives

and results, and a critical discussion. Others are quite loosely

organized (e.g. the Iranian example), require much reading before it

becomes clear what the issues were and how they could be handled, and

have so many subsections and headings that they rather read as a

purely descriptive report or diary. The book has a limited number of

references to the literature, in the sense that most publications

cited are authored by the Swedish group and their collaborators. There

is hardly any discussion of the findings in a more general worldwide

international context, which has probably been a deliberate choice.

This book has been a chance for Björk to express all his experiences,

which include great accomplishments, projects in very different

cultures around the world, continuous attempts to convince his

colleagues, engineers, public servants, politicians, and the larger

public, inevitably leading to successes but also frustrations. In this

sense, the book is also a historic account of the development of the

science of limnology in an era of strong environmental deterioration,

followed by public awareness and willingness to restore and by the

application of multidisciplinary knowledge in rehabilitation

projects. Sven Björk’s life and work was devoted to all of this, as he

showed in a colorful way in his book.

Jos T. A. Verhoeven

Restoration Ecology vol. 23, No. 6, November 2015, pp. 969-970