Synopsis Haut de page ↑

During the thirty years since the achievement of independence in many

African countries, Kenya has been prominent as an apparent exception

to the widespread political instability, social disturbance,

environmental degradation, famine and desertification which have

afflicted so many parts of the continent.

To a large extent this has been achieved because of the high

productivity of fertile soils in the humid highlands which form some

25 per cent of the country. Until very recently this has been

sufficient to sustain nearly 80 per cent of the Kenyan population,

which still has an annual growth rate near 4 per cent, amongst the

highest in the world. Land use pressure in the highlands has become

intense leading to subdivision of land into non-viable units, and

expansion onto steeply sloping lands of lower fertility and high

erosion hazard. The highlands cannot sustain significantly higher

population, so accommodation of future population growth must depend

on significantly increased utilization of the 75 per cent of the

country which is arid or semi-arid.

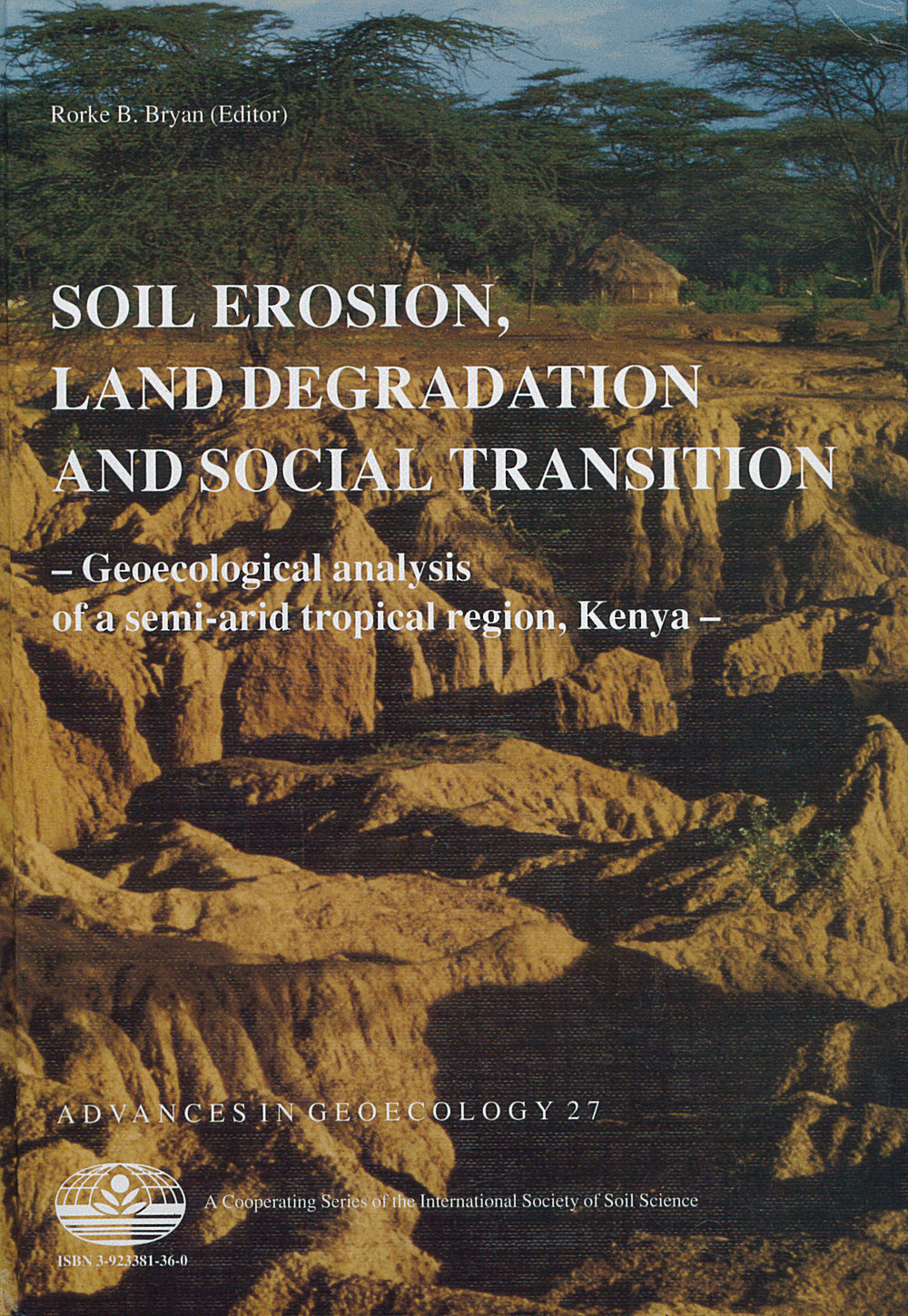

Past attempts to change land use and sustain increased population in

Kenyan drylands have not been very successful and have resulted in

serious land degradation, particularly in districts immediately

adjacent to the densely populated highlands, such as Machakos,

Baringo, Kajaido and Laikipia. Physical and ecological processes in

drylands differ fundamentally from these in more humid regions. The

productive capacity of drylands can be effectively utilised to

accommodate increased population without severe environmental

degradation only if land use is based on detailed understanding of

environmental processes and constraints. The papers collected in this

volume result from research carried out in Baringo District of Kenya

to provide basic information essential for land reclamation and

development of environmentally and socially appropriate land use

practices. Baringo has long been regarded as one of the most severely

degraded in Kenya. It was chosen for research because degradation

poses an immediate threat to the welfare of the population, and

because the district exemplifies within a small area many of the

environmental problems which have afflicted the Kenyan drylands and,

indeed, most dryland regions in sub-Saharan Africa. Baringo is

unusual, however, because there is already a considerable history of

scientific research and there is also a strong political will to find

appropriate solutions. Past attempts to reverse the cycle of

environmental deterioration in Baringo have not been very successful,

yet most of the ingredients necessary for implementation of

environmentally sustainable land use management now appear to be

present. With careful and innovative use of the information now

available, Baringo could become a model for effective land management

in many dryland regions in Africa.