Lichens dominate ca. 8% of the world's terrestrial ecosystems and play

important ecological roles in many other ecosystems, such as

foliicolous lichens in the tropics that provide a model system for

studying the development of their symbiotic relationship in the fi

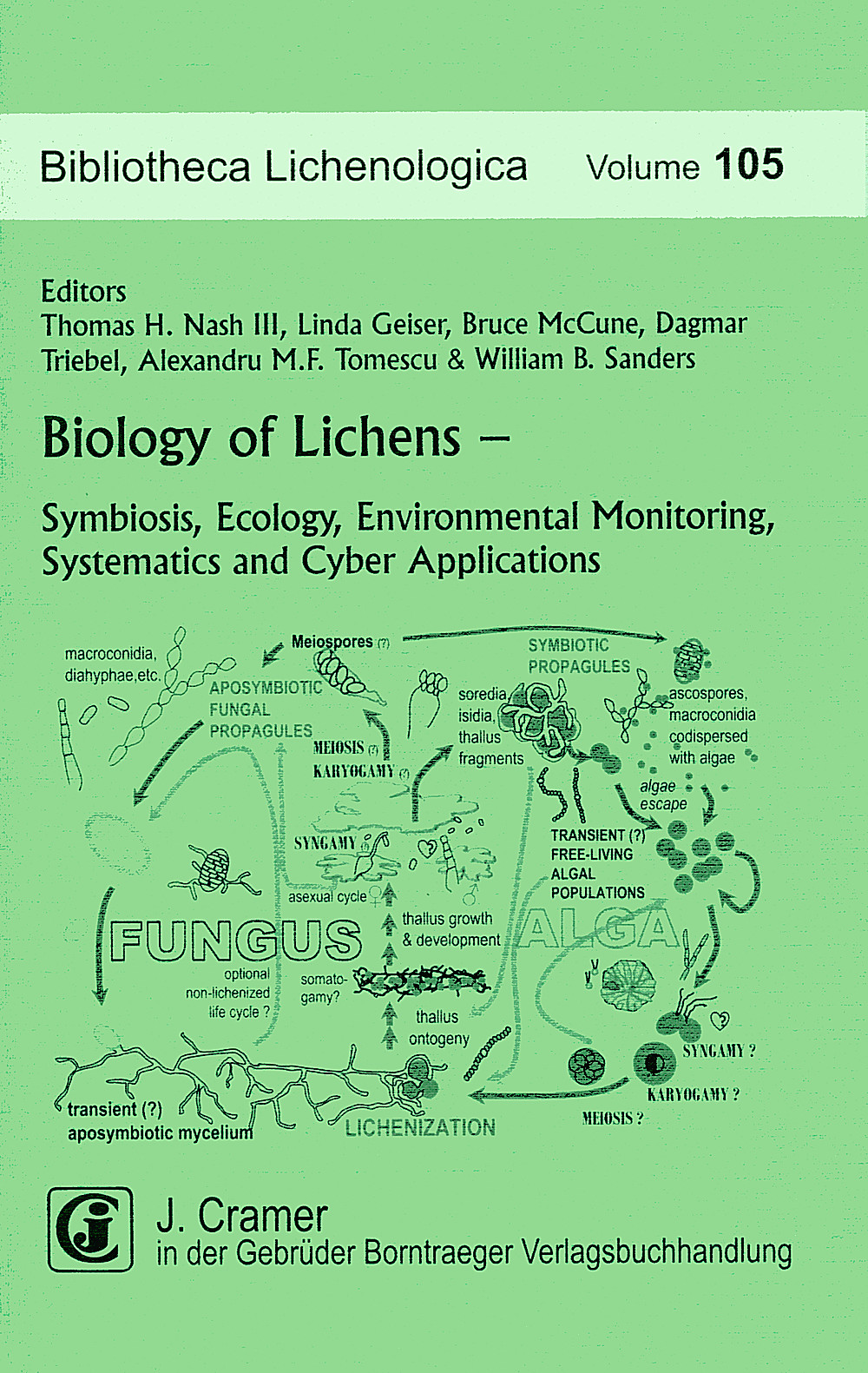

eld. In any discussion of symbiosis, the lichenized fungi play a

prominent role. Not only is a lichen a combination of fungus and

alga(e) and/or a cyanobacterium, but also hosts specifi c bacteria and

potentially other lichenicolous fungi.

Accordingly, this volume of Bibliotheca Lichenologica opens with a

modern review of symbiosis and closes with a paper on the selectivity

of the photobiont. The possible origin of the symbiosis from a

paleoecological perspective is also considered. The ecological role of

lichens in the widely distributed, arid soil crusts, as well as

several specifi c aspects of their community ecology, are also

discussed in other chapters.

For nearly two centuries lichens have been used in environmental

monitoring, especially in relation to air pollution, new aspects of

such monitoring relative to cumene hydroperoxide, Hg, NH3, O3, and

various organopollutants are covered in separate chapters. Several

systematic papers dealing with the Parmeliaceae and lichenicolous

fungi are also presented.

Cyber applications are now providing a wealth of information from

literature records back to the 1500s to vastly improved identifi

cation tools, to access to millions of collection records, and to

integrating biodiversity networks.

Review: International Lichenological Newsletter 43 (2)

top ↑

The most recent addition to Bibliotheca Lichenologica is a volume of

26 papers on a wide range of lichen studies most of them presented at

the 6th Symposium of the International Association for Lichenology

(IAL6) at Asilomar, California in 2008. The great variety of topics

might be explained best by citing the subgroups into which the papers

are arranged, giving the numbers of papers in every group in brackets:

Together and separate: the lives of the lichen symbionts (2),

Lichenicolous Fungi: taxonomy and diversity (2), Integrated Data

Networks in Lichenology (4), Air Pollution and Public Health (7),

Lichen Community Structure and Dynamics (4), Oldest Lichens and

Bryophytes (2), The World under Your Feet: biological soil crusts (2),

Mexican Parmeliaceae Systematics (2) and Selectivity in the Lichen

Symbiosis (1).

Four new species are described in the papers on lichenicolous fungi

and on Mexican Parmeliaceae, one in each paper, namely Stigmidium

californicum K. Knudsen & Kocourk., Dacampia lecaniae Kocourk. &

K. Knudsen, Canoparmelia tamaulipensis T. H. Nash & R. E. Pérez and

Melanohalea mexicana Essl. & R. Pérez. Unfortunately the name of the

author R. E. Pérez Pérez is given with different initials to those

cited above.

It is of course difficult and very subjective to select papers for

special treatment in such a review, but I found the two papers on

oldest lichens and bryophytes especially informative in relation to

new ideas and attempts to settle the question raised by the

title. Tomescu and co-workers paper on Simulating fossilization to

resolve the taxonomic affinities of thalloid fossils in Early Silurian

(ca. 425 Ma) terrestrial assemblages gives some insight into

experimental archaeology or palaeontology. Fossils from the

Appalachian Basin show clear patterns of plant and fungal growth, but

they are altered too much to name them satisfactorily. Therefore they

simulated fossilization under high pressures and heath with recent

lichens, bryophytes, algal crusts etc. and compared the resulting

structures with the fossils. By this it was found that structures of

recent lichens changed into the direction of the structures of the

fossils, giving further evidence that lichens might be involved in

fossilized structures older than those known from any vascular land

plants. The second paper in the section entitled Was the origin of the

lichen symbiosis triggered by declining atmospheric carbon dioxide

levels? by D.W. Schwartzman raised the question as to whether

lichenization was forced by algae growing on fungal mats because of

higher CO2 concentrations resulting from fungal respiration. This

hypothesis is supported to some extent from experimental studies by

various authors that refixation of photorespired carbon dioxide is

likely in lichens. The problem needs certainly further studies, some

suggested by the author, but nevertheless is an interesting aspect of

the evolution of lichens.

The book is certainly a need for lichenological libraries, but might

be a bit too heterogeneous to attract many private buyers.

The Editor

International Lichenological Newsletter 43 (2), page 14

Review: Acta Botanica Hungarica 53 (3-4), 2011

top ↑

The volume consists of papers selected mostly from topics presented

during the IAL6 Symposium, Asilomar, California in 2008. The 26 papers

included cover a wide range of research fields under 9 chapters. Just

as the symposium was organised together with bryologists, the paper on

thalloid fossils has bryological aspects, too. The origin and life

history of the symbiotic relationship forming lichens is treated in a

short review. In separate papers special attention is paid to

lichenicolous fungi and bacteria living together with lichens. The

selectivity of a frequent photobiont partner (Trebouxia spp.) is

studied in Ramalina farinacea.

Various projects (more recent or with considerable tradition) based on

internet applications are presented, e.g. the EU project KeyToNature

for producing and distributing interactive keys, the German project

LIAS on biodiversity information system (herbarium data, keys), the

project SYMBIOTA for American herbarium data and producing virtual

flora and the database “Recent literature on lichens”, which contains

today more than 40,000 bibliographic records (and new services) due to

the contributions of W. L. Culberson, R. S. Egan, Th. L. Esslinger,

P. Scholz, H. Sipman and E. Timdal and which has been available on the

World-Wide-Web as a free service since 1997.

The largest chapter is “Air pollution and public health”. After a ca

150 years history of acidic pollution (mostly due to sulphur dioxide

originating from traditional heating), nitrogen- containing air

pollutants (ammonia, nitric oxide) are in the focus of bioindication

studies now. Occurrence and concentration of heavy metals, ozone and

organic compounds are also studied by the help of lichens. Parmelia

sulcata, Ramalina farinacea, R. menziesii, Usnea filipendula,

Xanthoparmelia spp. and some others are among the investigated

species. The effects of global changes in environmental variables are

investigated at community level, using multivariate statistical

analysis. Communities of biological soil crusts are studied for their

fungi and also for their relation to various environmental factors and

for seasonal variation on their photosynthetic activity.

Systematics of lichens is represented only by two papers in this

volume, by two genera of Parmeliaceae from Mexico: Canoparmelia and

Melanohalea. The following species of lichens and lichenicolous fungi

are described slightly hidden among the several papers on various

other topics: Canoparmelia tamaulipensis T. H. Nash et R. E. Pérez,

Dacampia lecaniae Kocourk. et K. Knudsen, Melanohalea mexicana

Essl. et R. Pérez and Stigmidium californicum K. Knudsen et Kocourk.

A large number of publications related to presentations of IAL6 has

been published elsewhere. Nevertheless this volume summarises well the

topics occurred as lectures or posters in Asilomar, and in this way it

outlines the main streams of lichenology up to 2008.

E. FARKAS

Acta Botanica Hungarica 53 (3-4), 2011, p. 446

bespr.: Herzogia 24 (2), 2011

top ↑

Mit Band 105 dieser Reihe wurde erneut ein Sammelband von insgesamt 26

Einzelbeiträgen vorgelegt, von denen die meisten eine Auswahl von

Vorträgen darstellen, die zum 6. IAL-Symposium in Asilomar in

Kalifornien im Jahre 2008 gehalten wurden.

Unterteilt in einzelne Rubriken werden ganz unterschiedliche und

ziemlich heterogene Themenkomplexe behandelt beginnend mit der Rubrik

„ Together and separate: The lives of the lichen symbionts“ mit 2

Beiträgen zum Leben der Flechtensymbionten, deren Strategie zunächst

einzeln, dann der Prozess der Lichenisierung und somit der gesamte

Lebenszyklus betrachtet wird (Sanders). Im 2. Beitrag wird über den

Fortschritt bei der Kultur foliicoler Flechten auf Überzügen und der

erstaunlich kurzen Zeit von weniger als 65 Tagen, die

Gyalectidium-Arten bis zum Erreichen der asexuellen Reife benötigen,

berichtet. Im Kapitel „Lichenicolous Fungi: Taxonomy and Diversity“

werden in 2 Beiträgen von Kocourková & Knudsen eine neue

Stigmidium-Art von einer rindenbewohnenden Caloplaca aus Süd-

Kalifornien sowie eine neue Dacampia-Art von Lecania fuscella

beschrieben.

Dem Themenkomplex „Integrated Data Networks in Lichenology“ sind 4

Beiträge gewidmet. Randlande et al. berichten über das EU-Projekt

‚KeyToNature‘, eine Computer-gestütztes interaktives Instrument zur

Bestimmung von Organismen, incl. Flechten. Es wird gezeigt, dass im

Gegensatz zu gedruckten Bestimmungsschlüsseln eine Vielzahl anderer

Quellen wie Archive, Bilder u. ä. eingebunden werden können. Und in

dem digitalen Schlüssel ist nicht nur das Bild bzw. die Seite des

Bestimmungsergebnisses verlinkt, sondern auch die aller Zwischenstufen

des Bestimmungsprozesses. Die weiteren Beiträge berichten über

web-Service und die weitere Entwicklung der wohl allen bekannten

Datenbank „Recent literature on lichens“ (Timdal), die in München

laufenden Programme LIAS und Diversity Workbench (Triebel et al.) und

das Netzwerk SYMBIOTA (Nash III et al.), mit dessen Hilfe die

Kollektionen zahlreicher nordamerikanischer Herbarien in einer

virtuellen Flechtenflora dargestellt werden können, wobei die

beispiellose Integration taxonomischer Informationen es erlaubt, die

Ausgabe nutzerspezifisch anzupassen vom professionellen Taxonomen bis

zum Unterricht in Schulen.

Das umfangreichste Kapitel mit 7 Beiträgen beschäftigt sich mit „Air

Pollution and Public Health“. Hier soll nicht auf einzelne Beiträge

eingegangen werden. Es zeigt sich, das SO2 in den Untersuchungen keine

Rolle mehr spielt, stattdessen wird die Wirkung von NO, NH3, Ozon,

Quecksilber und halbflüchtigen organischen Verbindungen auf Flechten

untersucht, und ein Beitrag beschäftigt sich sogar mit seltenen

Erdelementen.

Im Kapitel „Lichen Community Structure and Dynamics“ sind 4 Beiträge

zusammengefasst, u. a. mit dem Thema, wie die Intensität der

Landnutzung in einem mediterranen Ökosystem die Diversität von

Flechten beeinflusst, die empfindlich auf zunehmende Verödung

bzw. Wüstenausbreitung reagieren. Aber auch die Modellierung der

Ökologie von Flechtengesellschaften ausgehend von ihrem

Photobiontentyp in Beziehung zur Sonneneinstrahlung und der in

unmittelbarer Umgebung stattfindenden Landnutzung ist ein

interessanter Ansatz. Die Reaktion von 16 kleinblättrigen

Flechtenarten auf Landschaftsform, Lichtregime und Luftverschmutzung

wurde in einer Langzeitstudie in den USA untersucht, wobei sich

zeigte, dass die einzelnen Arten recht unterschiedlich auf

Umweltfaktoren und deren Änderungen während der Untersuchungszeit

reagierten.

Im Kapitel „Oldest Lichens and Byophytes“ gibt es 2 Beiträge, von

denen sich einer damit beschäftigt, ob die stattgefundene

Flechtensymbiose durch sinkende CO2-Gehalte in der Atmosphäre vor sehr

langer Zeit (1 Billion Jahre) ausgelöst wurde; und es werden

Vorschläge unterbreitet, wie man diese Annahme durch Experimente

überprüfen kann.

„The world under Your Feet: Biological Soil Crusts“ titelt das nächste

Kapitel mit ebenfalls 2 Beiträgen, von denen sich einer mit den

pilzlichen Komponenten biologischer Bodenkrusten, der andere mit

mikroklimatischen Faktoren und photosynthetischer Aktivität von

Krustenflechten der semiariden südöstlichen Region Spaniens,

insbesondere mit Langzeitmessungen an Diploschistes diacapsis,

beschäftigt.

Im Kapitel „Mexican Parmeliaceae Systematics“ wird in einem Beitrag

die Gattung Canoparmelia in Mexico inklusive eines Schlüssels und

ausführlicher Beschreibungen der 13 Arten vorgestellt. Der 2. Artikel

widmet sich der Gattung Melanohalea in Mexico. Unter anderem wird auch

eine neue endemische Art beschrieben. Etwas irritierend ist hier, dass

im Schlüssel 2 Arten noch unter Melanelia aufgeführt sind, in der

Beschreibung dann aber als Melanohalea geführt werden. Das Gleiche

gilt für den Umstand, dass die Autorin Rosa Emilia Pérez Pérez, die an

beiden Artikeln beteiligt ist, im Inhaltsverzeichnis beide Male mit

den Initialen „R. L.“ geschrieben wurde.

Ein Beitrag in der Rubrik „Selectivity in the Lichen Symbiosis“ über

südeuropäische Populationen von Ramalina farinacea, die in einem

Thallus mit 2 unterschiedlichen Trebouxia- Arten leben, beschließt

diesen Band.

Alles in allem eine Zusammenstellung von durchaus interessanten

Beiträgen und Untersuchungsergebnissen, die jedoch thematisch sehr

breit gefächert sind, so dass es schwer fällt, den Band vorrangig

einer bestimmten Interessengruppe von Lichenologen zu empfehlen.

Regine Stordeur (Halle/S.)

Herzogia 24 (2), 2011, p. 393-394

Review: Inoculum 63 (3), June 2012

top ↑

Bibliotheca Lichenologica is a series including several monographs of

lichens within various taxonomic groups or from cryptogamically

unexplored geographic regions. To date, the series comprises 107

volumes, the earliest of which date back to the mid-1980s. Biology of

Lichens – Symbiosis, Ecology, Environmental Monitoring, Systematics

and Cyber Applications (Volume 105) includes selected papers related

to the International Association for Lichenology (IAL) 6 symposium

held in Asilomar, California in 2008. The first IAL symposium, held at

the University of Münster in 1986, was published in Volume 25 of

Bibliotheca Lichenologica, and IAL 3 and IAL 4 were published in

Volumes 68 and 82, respectively. Proceedings for IAL 2 were published

in Cryptogamic Botany, while Folia Cryptogamica Estonia contained

several contributions from IAL 5.

Biology of Lichens – Symbiosis, Ecology, Environmental Monitoring,

Systematics and Cyber Applications includes 26 papers compiled into 9

sections. As the title implies, the papers cover a broad spectrum of

lichen topics. This volume includes: holes in the symbiosis

literature; current advances in data networking as related to

lichenology; recent studies using lichens to quantify air pollution;

and reports of new species. The remaining third of the papers fit

roughly into the Ecology placeholder specified in the book subtitle,

yet have little true topical overlap.

As paper and poster presentations from an international symposium,

each of the studies offers novel research, which contributes to the

field of lichenology as a whole. The greatest original strength of

this compilation, however, is the section on data

networking. Significant progress has been made in the past two decades

to query the volumes of information amassed in the literature and in

herbaria on lichens. These search tools (e.g., LIAS, CNALH, RLL and

KeyToNature) are freely available to novices and experts alike, from

every corner of the earth where a lichen grows and piques someone’s

curiosity. This section of four informative papers provides a tidy

description of this work largely lacking from the lichen literature

(as evidenced from RLL and Mattick’s index).

My favorites among this melting pot of lichen bioinformation, however,

were the two papers by Tomescu et al. (2010) and Schwartzman

(2010). Tomescu and others’ inventive methodology to simulate

fossilization (i.e., 4 days of wet compression followed by 4 hours of

heating at 130°C), represents a novel way to understand the prevalence

of problematic cryptogamic fossils or paucity of non-vascular plant

and fungal fossils all together. Moreover, their study compliments

Schwartzman’s insights on the environmental triggers for the lichen

symbiosis. I found his paper a refreshing read of big ideas and little

data. His hypothesis transported me millions of years into the past,

and let me watch a gasping photobiont clutch its way around its

surroundings until finally collapsing into the hyphae of its partner

and taking in a deep breath.

The primary weakness of the book is its lack of coherence. Within 256

pages, there were 9 sections, which made the text read like a journal

rather than a book. Only one line on the inside cover clarifies that

this volume was intended to reflect the variety of lichen information

presented at IAL 6; nevertheless, as a single work it is a bit

disjointed. Upon reading the title and subtitle, I had anticipated a

general introduction on lichen biology providing a primer on a variety

of topics for new lichenologists. In retrospect, the title aptly

describes the contents of this text, yet its generality led me to

anticipate a book suitable for novices. Prolific esoteric lichen

terminology, the journal-like format, and studies narrowly focusing on

one geographic problem or taxonomic group limit its utility to this

audience. Ironically, this text may be more appropriate for

professional lichenologists who, in all likelihood, attended the IAL

symposium themselves. So if you prepare yourself for a journal-like

read, you will be rewarded with gems of lichen inquiry and

documentation of the technological transformation of our field.

Emily A Holt, Department of Biology, Utah Valley University

Inoculum 63 (3), June 2012

Table of Contents

top ↑

Together and separate: The lives of the lichen symbionts

SANDERS, W.B.: Together and separate: reconstructing life histories of

lichen symbionts 1

LARSEN, E.: Progress in culturing foliicolous lichens on coverslips 17

Lichenicolous Fungi: Taxonomy and Diversity

KNUDSEN, K. & KOCOURKOVÁ, J.: A new species of Stigmidium from

corticolous Caloplaca in southern California (USA) and Baja California

(Mexico) 25

KOCOURKOVÁ, J. & KNUDSEN, K.: A new species of Dacampia

(Dacampiaceae) on Lecania fuscella 33

Integrated Data Networks in Lichenology

RANDLANE, T., SAAG, A., MARTELLOS, S. & NIMIS, P.L.: Computer-aided,

interactive keys to lichens in the EU project KeyToNature, and related

resources 37

TIMDAL, E.: Recent literature on lichens: web services and further

developments 43

TRIEBEL, D., NEUBACHER, D., WEISS, M., HEINDL-TENHUNEN, B., NASH III,

T.H. & RAMBOLD, G.: Integrated biodiversity data networks for

lichenology - data flows and challenges 47

NASH III, T.H., GRIES, C. & GILBERT, E.: The consortium of North

American lichen herbaria: a virtual flora using the SYMBIOTA framework

57

Air Pollution and Public Health

PURVIS, W., GONZÁLEZ-MIQUEO, L., DOLGOPOLOVA, A., DUBBIN, W. &

UNSWORTH, C.: Use of rare earth element signatures in lichen, bark and

adjacent soils as indicators of sources of geological materials 65

WOLSELEY, P., SUTTON, M., LEITH, I. & VAN DIJK, N.: Epiphytic lichens

as indicators of ammonia concentrations across the UK 75

CATALÁ, M., GASULLA, F., PRADAS DEL REAL, A., GARCÍA-BREIJO, F.,

REIG-ARMIÑANA, J. & BARRENO, E.: Nitric oxide is involved in oxidative

stress during rehydration of Ramalina farinacea (L.) Ach. in the

presence of the oxidative air pollutant cumene hydroperoxide 87

SWEAT, K., GREMILLION, P.T. & NASH III, T.H.: Mercury concentrations

in the lichen Xanthoparmelia spp. in the greater Grand Canyon region

of Arizona, USA 93

BRANQUINHO, C., PINHO, P., DIAS, T., CRUZ, C., MÁGUAS, C. & MARTINS-

LOUÇÃO, M.A.: Lichen transplants at our service for atmospheric NH3

deposition assessments 103

RIDDELL, J., PADGETT, P.E. & NASH III, T.H.: Responses of the lichen

Ramalina menziesii Tayl. to ozone fumigations 113

GEISER, L., SCHRLAU, J., SIMONICH, S.M., GLAVICH, D. & DILLMAN, K.:

Lichens and conifer needles as indicators of airborne semi-volatile

organic compounds in western North America 125

Lichen Community Structure and Dynamics

GIORDANI, P., INCERTI, G., RIZZI, G., GINALDI, F., VIGLIONE, S.,

RELLINI, I., BRUNIALTI, G., MALASPINA, P. & MODENESI, P.: Land use

intensity drives the local variation of lichen diversity in

Mediterranean ecosystems sensitive to desertification 139

PINHO, P., BRANQUINHO, C. & MÁGUAS, C.: Modeling ecology of lichens

communities based on photobiont type in relation to potential solar

radiation and neighborhood land-use 149

MUCHNIK, E.: Evaluation of the significance of different abiotic

factors for species of the Parmeliaceae family in the Russian

forest-steppe zone 161

WILL-WOLF, S., NELSEN, M.P. & TREST, M.T.: Responses of small foliose

lichen species to landscape pattern, light regime, and air pollution

from a long-term study in upper Midwest USA 167

Oldest Lichens and Bryophytes

TOMESCU, A.M.F., TATE, R.W., MACK, N.G. & CALDER, V.J.: Simulating

fossilization to resolve the taxonomic affinities of thalloid fossils

in Early Silurian (ca. 425 Ma) terrestrial assemblages 183

SCHWARTZMAN, D.W.: Was the origin of the lichen symbiosis triggered by

declining atmospheric carbon dioxide levels? 191

The World under Your Feet: Biological Soil Crusts

BATES, S.T., GARCIA-PICHEL, F. & NASH III, T.H.: Fungal components of

biological soil crusts: insights from culture-dependent and culture-

independent studies 197

PINTADO, A., SANCHO, L.G., BLANQUER, J.M., GREEN, T.G.A. & LÁZARO, R.:

Microclimatic factors and photosynthetic activity of crustose lichens

from the semiarid southeast of Spain: long-term measurements for

Diploschistes diacapsis 211

Mexican Parmeliaceae Systematics

PÉREZ PÉREZ, R.L. & NASH III, T.H.: The genus Canoparmelia in Mexico

225

ESSLINGER, T.L. & PÉREZ PÉREZ, R.L.: The genus Melanohalea in Mexico,

including a new endemic species 239

Selectivity in the Lichen Symbiosis

DEL CAMPO, E.M., GIMENO, J., DE NOVA, J.P.G., CASANO, L.M., GASULLA,

F., GARCÍA-BREIJO, F., REIG-ARMIÑANA, J. & BARRENO, E.: South European

populations of Ramalina farinacea (L.) Ach. share different

Trebouxia algae 247